As a retired law enforcement officer, I want to share some facts and perspective on our profession and why it can feel like officers are often unheard. We’ll look at how many men and women wear the badge nationwide, what limits they face in voicing their opinions publicly, and how this one-sidedness affects public trust and policing.

By the Numbers: U.S. Law Enforcement Stats

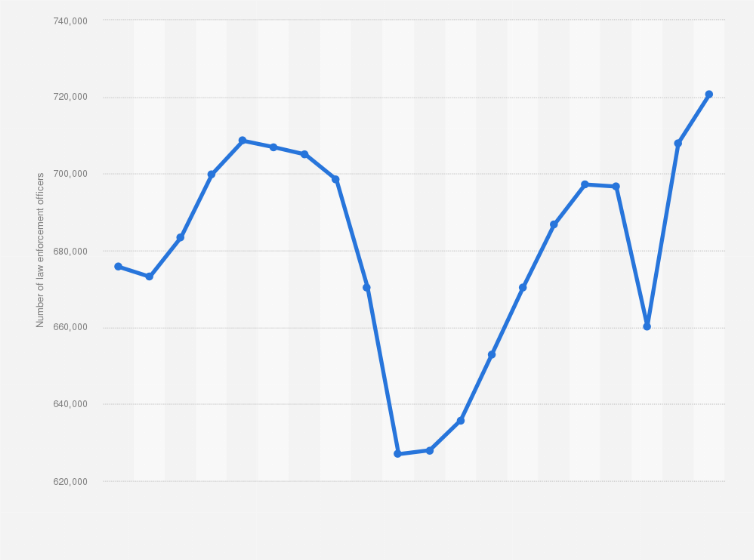

- Hundreds of thousands serve: There are over 900,000 sworn law enforcement officers now serving across the United Statesfedagent.com. (About 12% of these officers are femalefedagent.com.) This is the highest number of officers ever recorded.

- Nearly 18,000 agencies: Policing in America is very decentralized. Approximately 17,985 law enforcement agencies operate nationwide, including local police departments, county sheriff’s offices, state police, and federal agenciesen.wikipedia.org. Each agency has its own policies and jurisdiction, which means rules can vary, but some common themes emerge.

- Serving a large population: To put it in perspective, on average there are about 2.4 sworn officers per 1,000 inhabitants in the U.S.ucr.fbi.gov. These officers collectively protect a nation of over 330 million people, handling everything from emergency 911 calls to complex criminal investigations.

Restrictions on Officers’ Public Expression

- Speaking to media often requires approval: In most departments, officers are not free to speak to the press without authorization. For example, the Phoenix Police Department policy says officers may only talk to the media if designated by a supervisor, and “under no circumstances will information be released without first obtaining permission”brechner.org. Similarly, a policy from St. Louis explicitly states no employee may speak to news media without proper authorization, with violations subject to disciplinebrechner.org. In practice, this means frontline officers usually can’t directly correct a news story or publicly share their viewpoint unless a Public Information Officer (PIO) or supervisor clears it.

- Social media gag rules: Departments also impose social media policies that limit what officers can say online. Many agencies forbid posting anything that might reflect negatively on the department. In one city, the policy banned “negative comments on the internal operations of the department” or criticism of supervisors, and officers were disciplined for Facebook posts under this rulemasc.sc. (A court later struck down that overly broad policy for creating an “utter lack of transparency”masc.sc, but not before those officers faced punishment.) The bottom line is that active officers must be very cautious about what they post on personal social media if it touches on work.

- No politics in uniform: Generally, officers are prohibited from engaging in partisan political activity while on duty or in uniform, similar to rules for other government employeesjustice.gov. For instance, federal law (the Hatch Act) bars law enforcement officers from endorsing candidates or participating in political campaigns in their official capacityjustice.gov. Most local and state agencies have regulations to ensure officers remain neutral in public — you won’t see an on-duty officer publicly campaigning or rebutting political statements, because doing so could lead to serious penalties.

- “One voice” policy: Police departments typically want a single, consistent message. This is why information is funneled through official spokespeople. Nearly 42% of journalists report that access to rank-and-file police has gotten more difficult in the past decadebrechner.org. Reporters are often kept behind media lines at scenes and receive only curated briefingsbrechner.org. While this helps departments control accuracy and messaging, it also means the individual officer’s voice is often muted. An officer at the scene of a controversial incident can rarely give their account to the public without clearance – even if a news report is false, they generally “have the duty to remain silent” until an official statement is issued.

One-Sided Narratives and Public Perception

These communication restraints, though understandable for maintaining order and case integrity, can lead to a one-sided public narrative. When officers cannot freely speak, often the only story heard is from media reports, witnesses, or social media – which may be incomplete or even inaccurate.

- Misinformation fuels mistrust: False or misleading information about police incidents can spread quickly, and officers’ inability to immediately correct the record can be damaging. Studies note that misinformation can fuel public hostility toward the police, increase risks to officer safety, and disrupt police operationspolice1.com. Distorted narratives – especially in high-profile cases – undermine public trust in law enforcementpolice1.com. In today’s social media age, by the time the official police version comes out, much of the public may have already formed opinions based on the initial (and possibly false) reports.

- Transparency versus silence: Lack of an officer’s perspective can be misinterpreted as hiding the truth. Courts have even warned that overly broad gag orders on police speech can result in an “utter lack of transparency in law enforcement”masc.sc, which hurts credibility. People tend to trust institutions less when they feel information is being withheld. If only negative voices are heard and officers stay silent, the public understandably grows suspicious.

- Public confidence has dipped: In recent years, public confidence in the police has fallen to record lows, coinciding with a wave of high-profile incidents and intense media scrutiny. In 2020, confidence in law enforcement nationwide dropped to 48%, and by the following year it hit just 43% – the lowest level ever recordednews.gallup.com. (It has rebounded a bit since, but remains under historical norms.) While many factors drive public opinion, the prevalence of one-sided or negative narratives – without much pushback or context from the officers’ side – likely contributes to this decline in trust.

- Officers feel misrepresented: From the inside, police certainly feel this imbalance. A national Pew Research survey found that 81% of police officers believe the media treat police unfairlypewresearch.org. Think about that – eight in ten officers feel the press gives a skewed, negative portrayal. This sentiment is widespread among rank-and-file cops. When the people on the front lines feel the story out there is biased and they’re not allowed to respond, it creates frustration and morale problems within the force.

Why This One-Sidedness Matters for Policing

Trust and effectiveness are deeply connected in law enforcement. When the public only hears criticism or false reports and rarely the officer’s side, it erodes the trust that good policing relies on:

- Erosion of trust harms safety: Public trust is essential for effective policing, and when it erodes, it becomes much harder for police to do their jobs (police1.com). For example, if communities suspect the police aren’t being transparent or honest, witnesses may hesitate to come forward and victims might be less likely to call for help. In fact, a lack of trust between the community and law enforcement can make it difficult to solve violent crimes because solving cases often hinges on community cooperation (50statespublicsafety.us). Simply put, people are less willing to assist officers if they don’t have confidence in them.

- Impact on crime-fighting: Police effectiveness drops when the flow of information from the public dries up. Tips, leads, and community intelligence are crucial to preventing and solving crimes. If false narratives go unchecked and public sentiment turns hostile, officers lose the eyes and ears of the community. For instance, we’ve seen instances where misinformation spread online incited anger or even unrest, forcing police to divert resources to quell tensions. This reactive firefighting distracts from proactive policing. In contrast, when citizens trust their police, they share information more freely and work in partnership with us to keep neighborhoods safe.

- Morale and retention of officers: One-sided negativity doesn’t just affect the public—it affects officers on a personal level. Constant public criticism with no outlet to defend themselves can demoralize the good officers who show up each day to do a tough job. Many officers feel that their voices are constrained while falsehoods about them go unanswered, which can lead to frustration or burnout. Over time, low morale and a negative public image make it harder to retain experienced officers and recruit new ones. Policing is a challenging profession to begin with; if the only feedback officers hear is that they are doing wrong and they are muzzled from responding, it’s no surprise some choose to leave the force early. This “brain drain” can further hurt police effectiveness, as departments struggle to maintain adequate staffing of seasoned personnel.

In conclusion, the vast majority of America’s ~900,000 law enforcement officers serve with dedication, but they operate under strict rules that often prevent them from publicly sharing their side of the story. This is meant to maintain professionalism and unified messaging, but it has the side effect of creating a public dialogue that can feel very one-sided. As a retired officer, I believe acknowledging this dynamic is important. Balanced information and open communication could improve public understanding without compromising cases or discipline. If we want mutual respect between the community and the police, we must find ways for law enforcement to engage openly and honestly with the public. That means dispelling false narratives with facts and allowing officers to be human voices, not just silent uniforms. Bridging this communication gap can help restore trust, improve cooperation, and enhance overall policing effectiveness, making our communities safer for everyone.